Excerpts from the article published in the Journal of the Institute of Asian Studies, March 1999 – Here’s the full article “Murukan in the Indus Script’ on Roja Muthiah Library site http://rmrl.in/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/papers/22.pdf

IDEOGRAMS FOR ‘DEITY’ IN THE INDUS SCRIPT

1.1 The search for the possible occurrence of the name of a deity in the Indus Script has to be based on the following criteria : (a) A deity conceived to be human in form (as seen in the pictorial representations) is more likely to be depicted by an anthropomorphic ideogram than by syllabic writing. (b) the ideogram will occur with high frequency, and with especially higher relative frequency in dedicatory inscriptions on votive objects found in religious contexts. (c) The ideogram is likely to occur repetitively as part of fixed formulas possibly representing religious incantations.

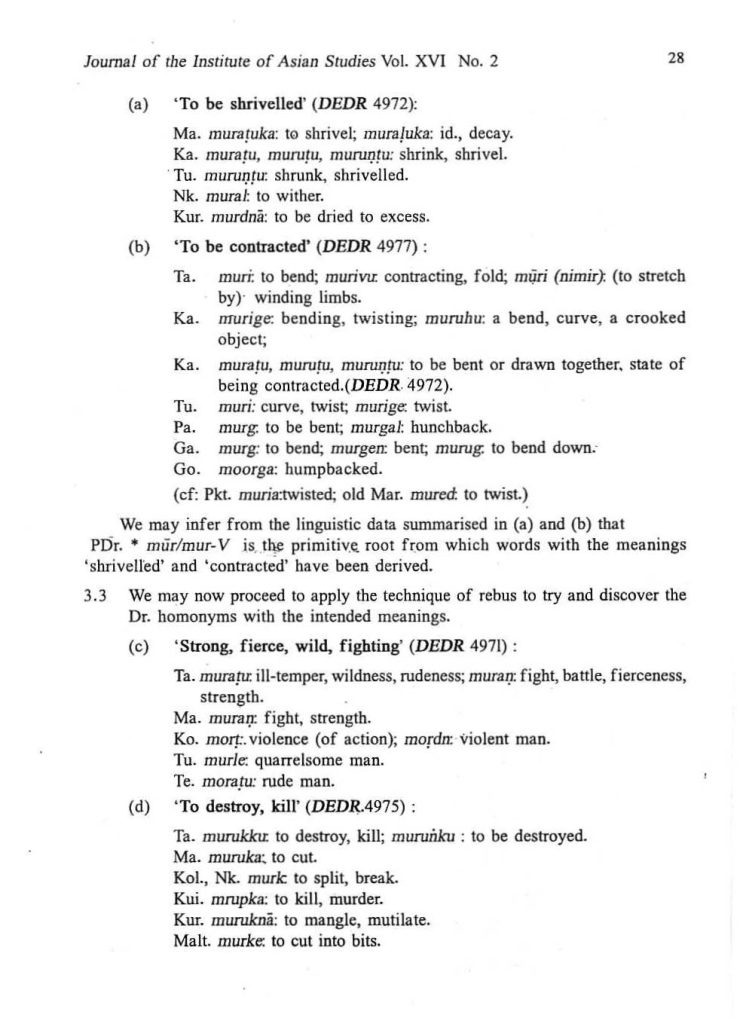

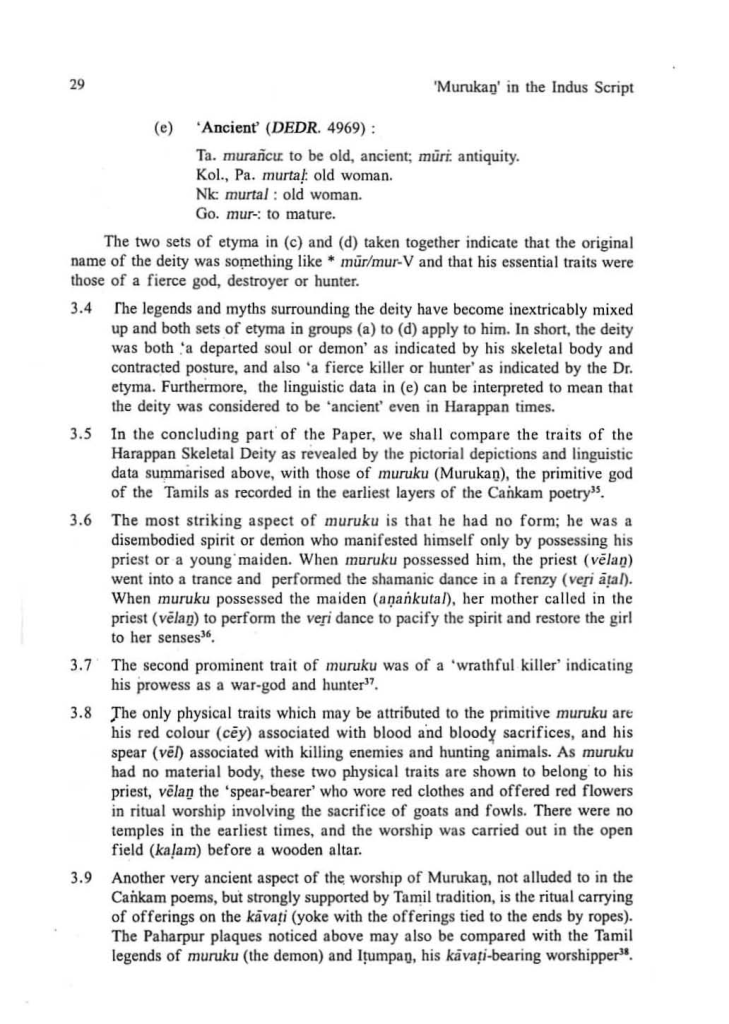

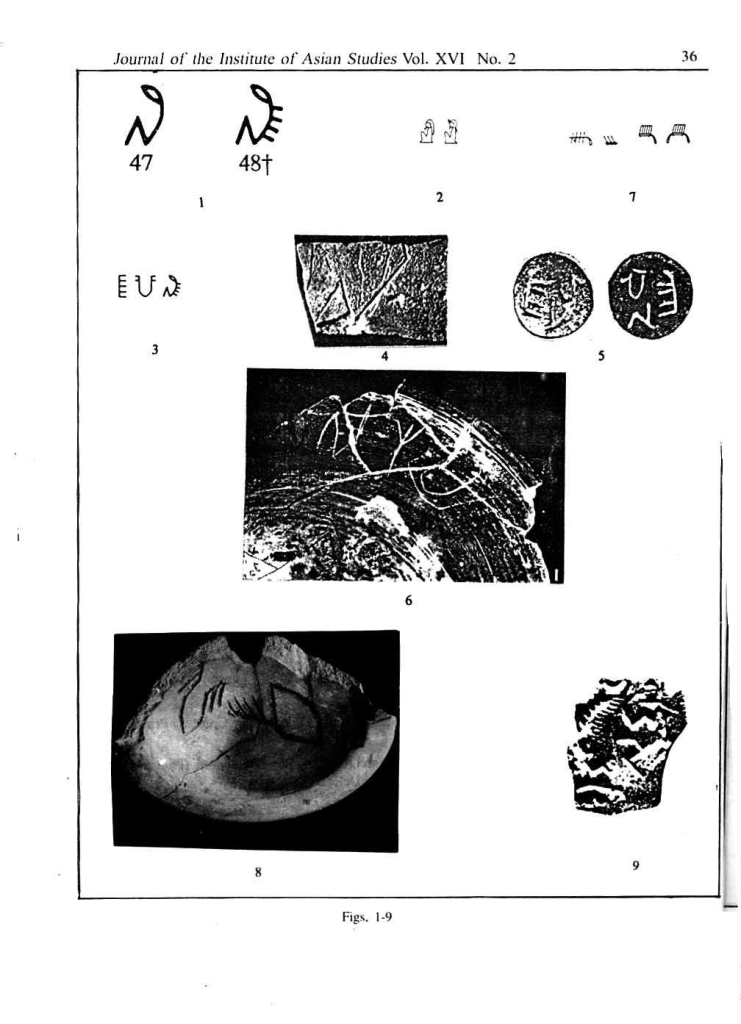

1.2 Signs 1-48 in the Indus Script are classified as ‘anthropomorphic’ on the basis of their iconography 2. There are two near·identical signs in this group, Nos. 47 and 48 (Fig. I) depicting seated personages reminiscent of very similar representations of deities in the Egyptian hieroglyphic script, in which a seated figure functions as the determinative for ‘god’ (Fig.2), and similar ideograms. modified by the addition of distinctive attributes. represent specific deities). On the basis of this’ analogy from a contemporary ideographic script. we may assume, as a working hypothesis to begin with, that Sign 47 of the Indus Script is the ideogram for ‘deity’ and that Sign 48, its modified form occurring with a much higher frequency, represents a particular ‘Deity’ characterised by the distinctive attribute added to the basic sign “. This identification receives some support from the pairing of these two signs in either order in l,he texts, probably to be read as ‘the deity X’ or ‘ X, the deity”.

1.3 The miniature tablets and sealings found at Harappa, especially from the lower (earlier) levels, are generally considered to be votive objects with dedicatory inscriptions incised or impressed on them, Sign 48, one of the more frequent signs in the Indus Script, occurs with a much higher relative frequency on the votive tablets and sealings’. Again, a text of. three signs with Sign 48 in the lead, which has the highest frequency of any 3-sign sequences in the who le of the Corpus of Indus Tex ts, occurs almost exclusively on the votive tablets and sealings, indicating that it is a ‘religious formula’ of some kind (Fig.3)·. It is Significant that in the Late Harappan Period at Kalibangan, the basic ideogram for ‘deity’ begins to appear as large sized graffiti on pottery suggestive of its use also as a religious symbol .

1.4 It is even more significant that the basic Indus ideogram for ‘deity’ survived as a religious symbol in the Post-Harappan Era. and occurs in regions far removed from the Harappan homeland:

(a) The frequent 3-sign text mentioned earlier (but with Sign 47 in the lead) is engraved on a seal found in the excavations at Vaisali, Bihar (~ig,5),·

(b) The basic Indus ideogram for ‘deity’ occurs often, presumably as a religious symbol, in the pottery graffiti from the Megalithic burials at Sanur in Tamilnadu (Fig.6)

SURVIVAL OF THE HARAPPAN SKELETAL DEITY IN LATER MYTHOLOGY AND ART TRADITIONS.

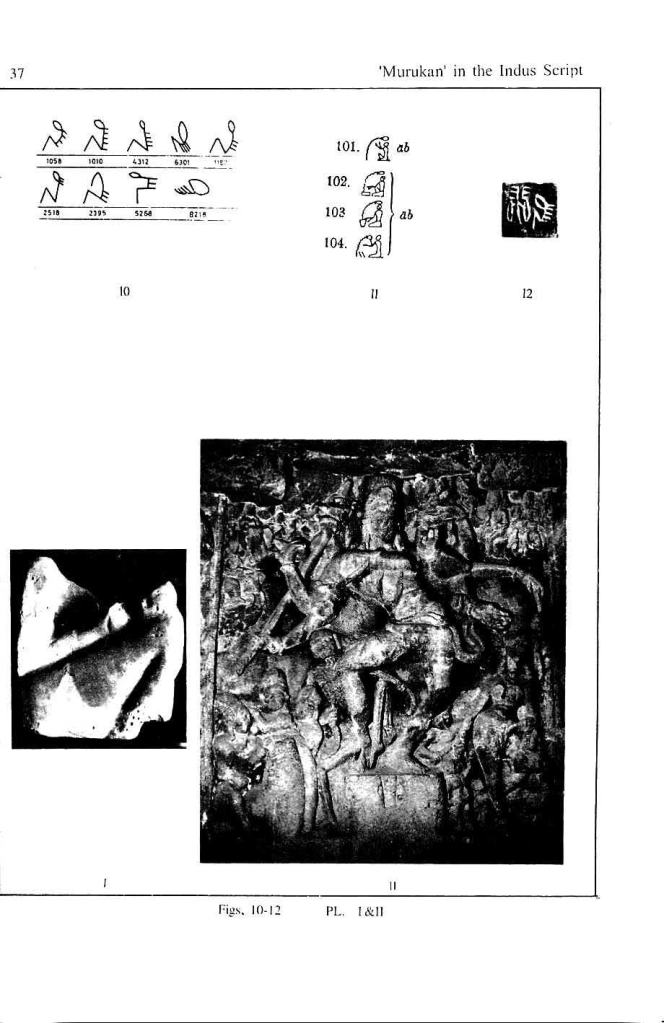

The identification of the ‘ Harappan Skeletal Deity’ leads directly to the recognition of its evolution as the ‘Emaciated Ascetics’ in later Indian mythology and art traditions.

The reason why Dadhyanca and Dadhikravan have names apparently derived from dadhi ‘curds’ may be explained on the basis of Dravidian etymology, assuming that these are loan-translations:

muci (Ta.): to grow thin, to be emaciated (DEDR 4903)

mucar~ mor (Ta.): curds, buttermilk (DEDR 4902)

murutu. muruntu (Ka.): to shrink, shrivel (DEDR 4972)

morata, morana (Skt.): sour buttermilk (connected to Dr. mucar, mor’ in DEDR 4902).

The Dravidian words for ’emaciated’ and ‘curds’ were homonymous. The Skt. names Dadhya iica and Dadhikravan appear to be the result of translating the wrong homophone, and thus ‘the emaciated one’ became ‘one fond of curds’!

The identification of the ‘ Harappan Skeletal Deity’ leads directly to the recognition of its evolution as the ‘Emaciated Ascetics’ in later Indian mythology and art traditions.

IDENTIFICATION OF TIlE HARAPPAN SKELETAL DEITY WITH DR. °MURUKU

The two defining characteristics of the pictorial depictions of the Harappan deity are (a) a skeletal body, and (b) bent and contracted posture. The Dravidian etymology with the nearest meanings arc as follows:

3.10 Much of the later Tamil literature, and virtually all the Tamil inscriptions and iconographic motifs have been heavily influenced by the Sanskritic traditions of Skanda-Karttikeya-Kumara and have very little in common with the primitive muruku except the name Murukan. Even the meaning of his name has undergone a radical transformation from muruku ‘ the demon or destroyer’ to Murukan] ‘ the beautiful one’, consistent with the later notion that gods must be ‘beautiful’ and demons ‘ ugly’, As P.L. Samy points out in his incisive study of Murukan in the Cankam works, there is no support for the rater meaning in the earliest poems. He derives muruku (Murukan) and murukku ‘ to destroy’ from Dravidian muru and endorses the identification of Murukan with

muradeva (a class of demons) mentioned in the Rigveda. as proposed by Karmarkar.

3.11 The muruku of the early Tamil society before the Age of Sanskritization was a primitive tribal god conceived as a ‘demon’ who possessed people arid as a ‘wrathful killer or hunter’. This characterisation of the earliest Tamil muruku is in complete accord with his descent from the Harappan Skeletal Deity with similar traits revealed through pictorial depictions, early myths and Dravidian linguistic data.

Excerpts From Iravatham Mahadevan’s article ‘A Note on the Muruku Sign of the Indus Script’, published in ‘The International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics’, June 2006 – Full article on Roja Muthiah Library Site – http://rmrl.in/wp-content/uploads/27-A-Note-on-the-Muruku-sign-of-the-Indus-script..pdf

The deity is represented as a skeletal body with a prominent row of ribs (in s. 48 only) and is shown seated on his haunches., body bent and contracted, with lower limbs folded and knees drawn up. The two related but distinct signs of the Indus script seem to have later coalesced into one symbol (resembling s. 47) outside the Harappan region. (For pictorial parallels from later limes, see illustrations in I. Mahadevan 1999).

According to the interpretation proposed here, the seated posture is suggestive of divinity and the skeletal body gives the linguistic clue to the name of the deity.

The basic Dravidian word mur (Ta. muri, Ka. muruhu, Pa., Ga. murg. Go. moorga etc., DEDR. 4977) means ‘to bend, contract, fold ‘ etc. Applying the technique of rebus, we get mur (Ta. murunku, murukku; Ma. murukka, Kol., Nk. murk, Malt. murke etc., DEDR 4975) meaning ‘to destroy, kill,

cut ‘, etc. Thus, the name of (he deity murukru and his characteristics ‘destroyer, killer’ are derived. The skeletal forms in the pictograms suggest that the god was conceived as a disembodied spirit.

Turning to the oldest layer of Tamil Sangam literature, we find that muruku/murukan was a spirit who manifested himself only by possessing his priest (velan) or young maidens. The priest performed the ven’ dance to pacify the spirit. The earliest references to muruku in Old Tamil portray

him as a ‘wrathful killer’ indicating his prowess as a war god and hunter (P.L Samy 1990).

Another important clue is the frequent association of the muruku and the load· bearer signs in the Indus Texts, paralleled by the association of murukan with kavadi in the Tamil society.

Another important clue is the frequent association of the muruku and the load· bearer signs in the Indus Texts, paralleled by the association of murukan with kavadi in the Tamil society. Outside the Indus valley, the muruku symbol has been found on a seal from VaisaIi in Bihar, dating probably from ca. 1100 BCE. (For details and previous references, see. I. Mahadevan 1999). In Tamil Nadu, the muruku symbol was first identified from the pottery graffiti at Sanur, a megalithic site. B.B. Lal (1960) correctly identified this symbol with sign 47 of the Indus script. In recent years, the

muruku symbol has turned up among pottery graffiti found at Mangudi (Tamil Nadu Department of Archaeology, 2003) and at Muciri, Kerala (V. Selvakumar ct al, in press).

All these occurrences on pottery belong to the Late Megalithic-Iron Age period overlapping-with the Early Historic Period (broadly, ca. 3 cent. BCE – 3 cent. CE). It is likely that the symbol retained the same meaning and sound value as at Harappa, though it occurs only as an isolated symbol on Megalithic pottery and not as part of a script. However, the latest discovery of an Indus Text with four signs engraved on a Neolithic polished stone celt (ca. 2000-1000 BCE) from Tamil Nadu is a revolutionary advance with far-reaching implications. Unlike the megalithic graffiti, the text on the Neolithic tool is in the classical Indus script characters. The first and the second signs (5. 48 and s. 342), viz. muruku and the ‘jar’ (to be read as -all) also form a well-known and very frequent combination on the Indus seals and sealings especially from Harappa. The third and fourth signs also occur in the Indus script (s. 367 and s. 301), but their value is not yet known. We can therefore conclude that the Harappans and the Neolithic people of Tamil country spoke the same language, viz. Dravidian.